Nothing prepared the Madison duo of Phil Humphrey and Jim Sundquist to be pop music stars in 1960. Absolutely nothing.

So when fame arrived, fleeting and forceful, they wallowed in it. The pair toured for seven rambunctious months and rubbed shoulders on the Billboard charts with Elvis Presley, the Everly Brothers and Roy Orbison.

“Naturally, we had to buy a nice car,” Sundquist says, laughing at the memory now. “We got a white, four-door ’59 Cadillac with big fins.”

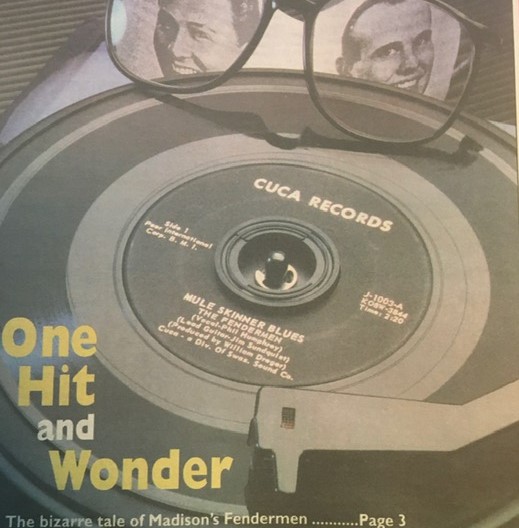

Known as the Fendermen, Humphrey and Sundquist recorded “Mule Skinner Blues” – a record with a rockabilly beat and yodel-like “hee-hee-haw-haw” chorus – in the basement of a Middleton home 35 years ago.

Sold originally from the trunk of a car, the record soared to No. 5 nationally and remains, according to chart historians at Record Research Inc., the biggest single ever by a Wisconsin-based act.

In a blink, the Fendermen went from performing before a dozen fans at Madison’s Ideal Bar on Atwood Avenue to sharing the bill of a Minneapolis auditorium show with Johnny Cash.

At the time, Humphrey and Sundquist were 22 years old and both married with two kids each. When they met in 1958, Humphrey drove a bread truck in Stoughton; Sundquist was a UW-Madison art student.

On June 11, 1960, they appeared on TV’s “American Bandstand” and the show’s staff arranged a set using two mules and chuckwagons.

Before the program, host Dick Clark met the Fendermen backstage. He beamed, shook their sweaty hands and told them enthusiastically: “What a wild song you guys have.”

* * *

Where are they now?

It’s a simple question on the 35th anniversary of their hit: What happened to Humphrey and Sundquist?

Well, their story is not always pretty or tidy.

Humphrey’s whereabouts, in fact, is not known.

Family, friends and business associates haven’t heard from him, in some cases, since the early ’60s. Sources ranging from records at his alma mater, Wauwatosa High School (class of ’56), to Sundquist failed to yield much help.

No one could verify whether he is alive.

Sundquist, meanwhile, lives in Minneapolis, where he is a nursing home’s activities director.

In a lengthy interview recently, he described his years of struggling in the music business after the Fendermen’s brief success. Alcohol and drug abuse plagued him and, by his own admission, nearly ended his life in the late ’80s.

On Oct. 7, 1990, he was born again. That, he says, helped him reconcile with his five children.

“Since I surrendered,” Sundquist says brightly, “my life has been so great you wouldn’t believe it.”

He remarried in 1991 and currently performs in a bluegrass gospel duo with his wife.

In concert, he still plays “Mule Skinner Blues,” and publicity materials for his cassette album “The Road to Heaven” clearly highlight his ties to the hit song.

The 57-year-old Sundquist (who was born on the same day in 1937 as Humphrey) has tried unsuccessfully to track down his former partner.

He talks about Humphrey in the present tense but admits that Humphrey’s fate is unclear.

“And that,” he says, “is one big mystery.”

* * *

Humphrey and Sundquist split up in early 1961, after “Mule Skinner’s” follow-up single, “Don’t You Just Know It,” failed to crack the Top 100.

“We didn’t see eye to eye,” Sundquist says. “I love Phil Humphrey and he was a great entertainer. But I don’t think he thought highly of me as a guitar player.

“More than anything, he wanted to form a big (pop/rock) band. I wanted more of the old Johnny Cash sound. Keep it simple, you know. He wanted something more elaborate. That’s what it boiled down to.”

Both men continued to perform separately in nightclubs for several years: Humphrey with a Canadian band, the New Fendermen; Sundquist with the Mule Skinners and later Jim Sun and the Radiants.

What Sundquist has heard of Humphrey’s experiences in the ’60s seem to mirror Sundquist’s turmoil. Sundquist’s marriage dissolved, and the music business never opened its arms to him again.

“I went out on the road and got into booze and dope,” Sundquist says. “I believe the same thing happened to Phil.”

Various associates of Humphrey from the ’60s paint a depressing picture. One heard that Humphrey spent time in a Mexican prison.

Humphrey’s daughter may still live in the Madison area, but attempts to reach her were unsuccessful. (A person who spoke to her about 18 months ago says Humphrey’s daughter had not seen her father since the ’60s.)

Oddly, the last person to claim that he’s talked to Humphrey is former one-hit wonder Donnie Brooks (“Mission Bell”). A promoter and performer, Brooks was putting together a nostalgia show in 1986 when he says he talked to Humphrey in Los Angeles.

Humphrey told Brooks, “I’ve been born again and I won’t play music.”

* * *

In fall 1959, Jim Kirchstein says, he pulled the Fendermen’s first recording of “Mule Skinner Blues” off a shelf where it sat at his fledgling Cuca Records label in Sauk City.

“I thought the song was a gimmick,” says Kirchstein, now an electrical engineer for UW System administration. “I really didn’t think it would work on the pop market as much as it did.”

“Mule Skinner” (the title refers to a person who drives mules) was written by country star Jimmie Rodgers in 1931. Sundquist says he had heard it on a bluegrass record.

Kirchstein printed the single and sent up to 100 copies to radio stations nationwide. Reaction to the song was quiet, until it received airplay at a University of Nebraska station. Then a La Crosse disc jockey backed the song and hired the band for gigs.

That’s where the Fendermen met Amos Heilicher, owner of Soma Records in Minneapolis. Heilicher helped to push the record to national attention – and it is rumored that he paid $800 to guarantee the Fendermen a spot on “American Bandstand.”

A wheeler-dealer by all accounts, Heilicher “leased” the rights to “Mule Skinner Blues” from Kirchstein, then changed the record’s flipside because Kirchstein owned publishing rights to it.

Kirchstein, though, never received his financial stake from Heilicher until the pair settled out of court in 1962 for $50,000, much of which went toward Kirchstein’s legal expenses. (Still, Kirchstein used funds from the settlement to turn Cuca Records into a prominent regional label.)

The Fendermen, meanwhile, never realized that promotion costs for “Mule Skinner Blues” were coming out of their pocket, not Heilicher’s. As a result, Humphrey and Sundquist made their money from a relentless string of profitable one-night stands in ballrooms across the country.

Court battles over “Mule Skinner’s” profits from nearly one million sales kept a Fendermen album from being manufactured until 1962, when it was released in obscurity.

* * *

To find a copy of “Mule Skinner Blues” now, it’s easiest to search a bin of used vinyl albums featuring novelty songs. Last month, Resale Records on Madison’s east side tracked it down on a 1979 K-Tel album called “Goofy Greats.”

“Mule Skinner” features no bass or drums, just two voices, two guitars and enough echo to shake a tree.

The Fendermen performed “Mule Skinner Blues” at every gig during their career, including their first appearance at the Oats Bin in Stoughton, where they were paid $5 and given free beer. Weeks later, they’d make $11 each at Madison’s Ideal Bar.

Hearing Sundquist tenderly describe these moments, it’s apparent that he still treasures his experiences with the Fendermen.

“Whenever our time onstage was almost over,” Sundquist recalls, “I’d say, `It’s time, Phil, let’s hit ’em with it.’ That’s when we’d play `Mule Skinner Blues’ and everybody in the crowd would love it.”

Aftermath of the story: Finding the missing member of the Fendermen

(March 16, 1995)

Two weeks ago, Phil Humphey was told “Guess what, they think you’re dead.”

That comment came from Humphrey’s high school friend, who lives in southern Wisconsin, speaking to Humphrey for the first time in 10 years.

Using a variety of sources, the friend tracked down Humphrey in Canada to send him the Feb. 23 Wisconsin State Journal story, titled “One hit and wonder: The bizarre tale of the Fendermen.”

A Madison music duo, the Fendermen enjoyed a major hit single with the rockabilly novelty song, “Mule Skinner Blues,” in 1960.

It’s still the highest-charting record – having reached No. 5 on the Billboard charts – by a Wisconsin-based band.

The story focused on singer Phil Humphrey and guitarist Jim Sundquist. Sundquist is living in Minneapolis and spoke at length about the short-lived band.

Humphrey, though, was a mystery – several family, friends and business associates had not heard from him since the mid-’60s. No one knew whether he was alive.

Late last week, I was given Humphrey’s phone number in Canada. Humphrey later asked to keep the specific spot private.

After initial hesitation – “I’d rather not be found,” Humphrey said; “(the Fendermen are) almost like a past life” – he agreed to discuss his career. Humphrey, now 57, described his distaste for the music business, which he believes withheld enormous profits from him for “Mule Skinner Blues.”

“We had one hit and my lawyers told me it sold more than a couple million copies,” Humphrey said. “We didn’t get anywhere near what we deserved” financially.

Humphrey recalled the relentless touring in 1960, “averaging 2,000 miles a week driving but we were young and we had a good time.”

Wanting to work with a bigger band, Humphrey split with Sundquist in 1961 and fronted a six-piece Canadian group.

“We traveled, performed at clubs and had go-go girls in cages (as part of the show) until 1966,” he said.

“At that time, I was pretty well out of it – alcohol and drugs and all that. I married one of the go-go dancers and had a child and she had enough foresight to say, `Look, either you’re going to quit this thing or I’m out of here.’ So I sold the name of the band for $20 and we walked away from it and went to California and started over.

“That was the last anyone had ever heard of me.”

Humphrey said he was born again in 1968, and his family moved to Canada in 1971. He’s still married to the former go-go dancer, and they have six adult children. He runs a home renovation business.

Looking back on his brief time in the limelight, Humphrey is frank.

“I was not a nice person … I was pretty well out of it for much of the time.

“For instance, (country legend) Red Foley phoned me (in 1960) from the Grand Ole Opry and I hung up on him. I told him, `I’m not a hillbilly singer.’ That’s something I’ve regretted for a long time. He phoned me twice, and I told him to stuff it.

“I thought I was a blues singer, and I had this vision of a band with saxophones that I eventually got, but no more hits after that.”

Humphrey keeps no mementos of his career as a member of the Fendermen.

“We moved a lot, and I didn’t have room to carry it and all the pictures so I threw ’em out.”

Could he still remember the words to “Mule Skinner Blues” today?

“Oh, sure. It was wonderful,” he said, then laughs. “In the end, my band was doing it four or five times a night.”